My friend Jocelyn Steelman died this week. She was 46 years old, a loving wife to Elliot and adoring mother of two boys, 13-year-old Jacob and 10-year-old Felix.

We met Jocelyn and Elliot 10 years ago when our oldest boys were in pre-school together. It was a busy and challenging and special time – the demands of young kids, full-time jobs, and managing city life. These were things our friend group navigated together. We shared notes on the best museums for play dates, the latest sports or music classes, favorite playgrounds, how to manipulate our strollers on the subway, where to eat out with kids, the terror of young ones on scooters heading for busy street corners, and so on.

She was part of a group that I leaned on innumerable times when things blew up in my professional life. Can someone drop Yates at this class? Can someone watch Yardley immediately? Jocelyn related to it all as she was a rising star at Moody’s and had the same work-life balance issues I did – a situation we discussed countless times. Jocelyn and Elliot were both busy professionals who happened to live right around the corner from us in New York City, which led to many fun dinners together on the usual topics: How is work/how are the kids/how are we managing any of this??

Our friend group would get together for drinks on the Upper West Side or for our famous flip-cup competitions. It was guys against gals, and we were serious about winning – headbands, slogans, the whole bit. She was an excellent flip-cupper. The gals always won.

We went to Jocelyn’s parents’ home on Long Island and met her mom and dad. They clearly adored Jocelyn and her family and, as they were committed Democrats, we had some spirited discussions about politics and Fox News (where I worked at the time). They, like their daughter, had such vitality, humor, and wit. Jocelyn was logical, smart, organized, and driven but also fun and quick to laugh with a beautiful smile. When I think of her, I picture her smiling. How many people can you say that about?

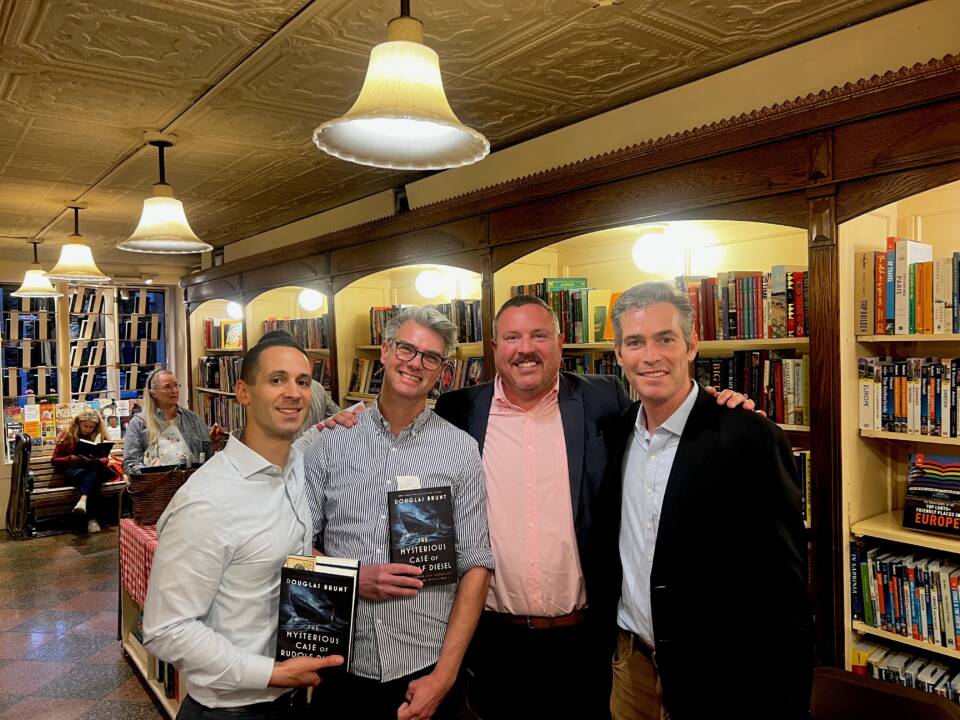

Elliot was always the sentimental one – the dad who never missed a game or a chance to tell you about the Baltimore Orioles; a successful lawyer whose Navy dad toughened him up but who, behind the scenes, is all kindness, warmth, and heart. Two weeks ago, Elliot came to a book signing Doug was appearing at on the Upper East Side. Someone took a photo of them. Elliot is next to Doug, taking time out of his busy life to support a friend, to reconnect, to say, in the way showing up will do, ‘I care about you and our friendship.’ It meant a lot to Doug to see him there, and we resolved to reach out to him and Jocelyn soon for dinner.

Days later, Jocelyn died. It’s not yet clear what caused it – maybe her heart. Jocelyn was the picture of health. Why would God do this? To her? To Elliot? To those young boys? What purpose could possibly be served here, and what does it even matter when her death feels so unjust?

On Tuesday, we attended her funeral. Sitting in the Congregation Rodeph Sholom synagogue, I noticed something. Virtually everyone there was young. There was almost no grey hair. The entire fifth and ninth grade classes from the boys’ school showed up. There were hundreds of people there, most in the prime of their lives. This is not what funerals are supposed to look like. I happened to be seated in an area with mostly men – not a single one with a dry eye. The tears flowed liberally, men and women alike.

The ceremony was incredibly moving. The psalms sung by the cantor and his intonation of them felt soulful and profound. I noticed the lack of music or sound as the family made their way through the synagogue, with the pallbearers carrying the casket. It was a muted blonde color, and it reminded me of Jocelyn with her soft golden hair. She shouldn’t be in there. We shouldn’t be here. Her sons should not have to stand here and mourn their mother.

Elliot stood up to eulogize his wife of 20 years and the mere sight of this courageous act took our collective breath away. I was reminded of stories about Jocelyn that I first heard years ago and learned some new ones as well. They met in college. She was 18; he was 17. As the years went by, he had fun reminding her of the age difference. He was from Baltimore and not particularly well dressed; she was from New York – sophisticated and worldly, always dressed in black. They fell in love while spending a semester abroad in Florence, Italy, and introduced each other to their parents upon returning home. The Freedmans and the Steelmans became immediate family.

A wedding at the Plaza and two sons later, Elliot spoke of Jocelyn’s stellar work at Moody’s and her tireless advocacy for her sons’ well-being, whether at school, at home, or on the baseball diamond. More than one umpire came to know first-hand what we already knew about our friend: Jocelyn was no shrinking violet. Elliot reminded his boys how much their mother loved them, and their muffled cries were like daggers through the heart of those bearing witness. Elliot cracked a joke here and there – managing to find a smile. What a message for his sons: It’s okay to laugh, even now. He promised them: “We will be happy again… We will travel the world together.” It was clearly a dream the four of them had shared. Now it will be a trio, missing their mother and wife.

The burial was a shock to me. I had never participated in a burial where the mourners shovel dirt onto the casket, a Jewish tradition meant to show respect for the dead. Elliot was the first to do this, and I marveled at the strength of this man, who just 72 hours after finding his vibrant, loving wife non-responsive now had to cast the first mounds of earth onto the coffin bearing her remains. Impossible. And yet he did it. He held his boys and his parents and his friends, and he did it. He made it through and their extended family helped him, holding one another and crying, sharing their love and support and grief.

I would like to tell you that as I said goodbye to the family later that day after attending Shiva, I had a better understanding of what it all meant. Is there a lesson in something so tragic? Anything I could come up with felt trite and unsatisfying. The rabbi’s words were the closest I’ve come to an answer. She said that in these moments, one doesn’t need to search for false comforts. Sometimes it’s enough to marvel that a heart completely broken can still yet beat. For Elliot, Jacob, and Felix that will have to be enough, for now.

Having lost my own dad when I was 15, I know first-hand that this kind of loss – as devastating as it is – can change how we move forward. What decisions will these boys make now that they may not have made without this tragedy? Will they hold themselves to a higher standard of happiness with the knowledge that life really is frustratingly short? Might they move on in the future from an unsatisfactory job or relationship because they know on a gut-level that no tomorrow is promised? Will their lives, made so challenging by the sudden loss of their mother at a tender age, wind up more aligned with their needs because they’ve taken to heart how there is no time to waste? That is my hope for them.

In the meantime I’m thinking of the song I always come to in the wake of a sudden tragedy. It’s the song my dad used to play for us on his guitar around the campfire. It’s a song that happened to appear in my own guitar playbook one day when I was missing him in my twenties and asking for a sign. It’s a song that just happened to be playing on the radio after my sister’s death last year. It’s John Denver’s “Today”:

Today, while the blossom still clings to the vine

I’ll taste your strawberries, I’ll drink your sweet wine.

A million tomorrows shall all pass away

‘Ere I forget all the joy that is mine, today.